Which of these players, if either, do you think belongs in the Baseball Hall of Fame?

- In nearly 17 major league years, Outfielder A had 2,349 hits, scored 1,259 runs, hit 121 homers, drove in 1,024 runs, stole 237 bases, with a .312 batting average.

- In nearly 18 seasons, Outfielder B had 2,246 hits, scored 1,156 runs, hit 227 homers, drove in 1,062 runs, stole 276 bases, with a .287 batting average.

Let’s start with this clear conclusion: Both players are borderline Hall of Famers, not likely to get voted into Cooperstown by the Baseball Writers Association of America, but possibly candidates for eventual election by a Veterans Committee.

Outfielder A has a slight advantage in hits and runs and a clear advantage in batting average. Outfielder B has a slight advantage in RBI, a clear advantage in stolen bases and a big advantage in homers.

If you were to choose one over the other for the Hall of Fame, it might be based on a few really spectacular years or consistency, perhaps defensive excellence, perhaps some special achievement that doesn’t show up in the stats. But based on the whole career, these two players are closely comparable.

Here’s who the two players are:

- Player A is the average career of the 19 20th-Century white outfielders elected to the Hall of Fame by Veterans Committees. All but two played all or most of their careers before baseball integrated in 1947.

- Player B is the average career of 19 African American and Latino players who are getting little or no consideration for the Hall of Fame.

Here are the 19 white outfielders, every one of them a Hall of Famer: Richie Ashburn, Earl Averill, Max Carey, Fred Clarke, Earle Combs, Sam Crawford, Kiki Cuyler, Elmer Flick, Goose Goslin, Chick Hafey, Harry Hooper, Chuck Klein, Heinie Manush, Sam Rice, Edd Roush, Enos Slaughter, Lloyd Waner, Hack Wilson and Ross Youngs.

Here are the 19 African American and Latino players in my comparison: Matty Alou, Harold Baines, Albert Belle, Bobby Bonds, Joe Carter, José Cruz, Chili Davis, Tommy Davis, Curt Flood, George Foster, Ken Griffey Sr., Kenny Lofton, Willie McGee, Al Oliver, Dave Parker, Vada Pinson, Tim Raines, Bernie Williams and Willie Wilson.

I didn’t include Cubans Tony Oliva and Minnie Miñoso, whom I compared to a smaller selection of Segregation Era Hall of Fame outfielders in the first post in this series.

I’m not sure those are the best 19 other minority outfielders who are eligible for the Hall of Fame but have been rejected by the writers and aren’t in Cooperstown yet. I originally started with 27 but cut Felipe Alou, Don Baylor, Vince Coleman, Willie Davis, Amos Otis, Ken Singleton, Reggie Smith and Jim Wynn. I’m not sure I cut the right players from the list, but even with all 27, they stacked up similarly to the white Hall of Famers, comparable and leading them in homers, RBI and steals while lagging behind the whites in batting average, hits and runs.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying that all of these African American and Latino players belong in the Hall of Fame. I think most of them don’t. But it’s absolutely impossible to justify that all of these white outfielders are in the Hall of Fame and none of the outfielders of color is in the Hall. Especially when I add that, even though baseball was integrated nearly 70 years ago, Larry Doby is the only outfielder of color elected to the Hall by the Veterans Committee. All the others were easy enough calls that the writers voted them in.

Not only are the players’ careers statistically comparable, but the white players achieved their stats without facing all the best pitchers of their times. Many of the minority players achieved their stats in an era of expansion, and that’s sometimes used as an excuse to discount their achievements. But the pool of potential major leaguers expanded hugely with integration, welcoming not only African Americans but players from the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America and eventually Asia.

No outfielders in the white group matched Parker’s 339 homers, and Goslin and Crawford are the only ones with more RBI than Parker’s 1,493. Those two, Rice and Wheat are the only ones with more hits than Parker’s 2,712. Klein is the only one to match Parker’s achievements of leading his league in batting average, RBI and hits.

Maybe Parker’s cocaine abuse explains his long wait to enter Cooperstown (I think he’ll make it someday, though the Expansion Era Committee has already turned him down).

But Matty Alou was an exemplary person and player. The standards for the Hall of Fame once allowed Hafey, with a .317 batting average but only 1,466 hits, 164 homers, 70 steals and less than 900 runs and RBI. But once black and Latin players became eligible, the Hall’s standards are so high that Alou, with a .307 batting average and more hits, runs and steals, gets no consideration? Each man was a batting champion once, but Alou led his league in hits and Hafey never did.

Carey had a mediocre batting average for his day, .285, and had no power. But he played 20 years, got 2,665 hits, scored 1,545 runs and stole 738 bases. How is that worthy of the Hall of Fame, but Raines isn’t, with a higher batting average, more power, more runs, more stolen bases and nearly as many hits? Actually Raines will probably make the Hall of Fame someday. He’s still on the writers’ ballot, getting 55 percent on this year’s ballot, with two years left for writers’ consideration. Carey peaked at 51 percent of the writers’ vote and was elected by the Veterans Committee. Time will ease some of this injustice for Raines and some other minority players.

But Harold Baines has more hits than all but three of the white outfielders and more RBI than any of them. He lasted only five years on the writers’ ballot, peaking at 6 percent of the vote. As primarily a designated hitter, Baines faces a double prejudice, but he played more than 1,000 games in the outfield.

Since this blog is usually about the Yankees, I’ll compare two centerfielders who played in different Yankee championship eras. Combs played for the Murder’s Row Yankees, best known for his teammates Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, back when the majors were all white. Williams also was a teammate of two all-time greats: Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera. Combs’ stellar batting average, .325, was excellent even for his time. Williams’ batting average was a solid .297. Williams had more runs, hits, homers, RBI and stolen bases than Combs, a higher slugging percentage and a nearly identical OPS (Combs was .859, Williams .858). Combs led his league once in hits, Williams once in batting average. Combs peaked at 16 percent in the writers’ vote and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1970 by the Veterans Committee. Williams fell off the ballot after two years, never reaching 10 percent.

I could continue with the comparisons, but here’s the bottom line: the African American and Hispanic outfielders I named had closely comparable careers to the white outfielders, individually and collectively. But every one of the whites is in the Hall of Fame and most of the minority outfielders will never make it unless selection voting changes dramatically.

Beyond the career statistical similarities, the black and Latin players have more special achievements that might give them a little extra boost in Hall of Fame consideration:

- Bonds’ record (shared with his son) of four seasons hitting 30 homers and stealing 30 bases.

- Flood’s challenge of baseball’s reserve clause.

- Williams’ record for post-season career RBI (and high rankings in other post-season career stats).

- Carter’s World Series-winning homer.

Klein won a Triple Crown and Wilson holds the all-time RBI record, but I can’t think of another special achievement among the white group.

Both groups have interesting family connections: Waner and his brother, Paul, are the only brothers in the Hall of Fame. Alou was one of three brothers in the majors at the same time, once playing in the same outfield for the Giants. Cruz had two brothers and a son who played in the majors. Averill, Bonds and Griffey all had sons in the majors. Ken Griffey Jr. is a certain Hall of Famer and Barry Bonds would be if not for suspicions that he used performance-enhancing drugs (see my note on that topic at the end of the post).

But the family connections are just interesting. Even in Waner’s case, I don’t think his relationship to Paul played a factor in his Hall of Fame. His career accomplishments fit in well with other Veterans Committee selections of his time.

Catchers

Let’s do a similar, but simpler, comparison between African American catcher Elston Howard, who played mostly for the Yankees, and the four white catchers elected by Veterans Committees: Roger Bresnahan, Rick Ferrell, Ernie Lombardi, Ray Schalk.

All four Hall of Famers played their careers entirely in segregated baseball, except for Lombardi and Ferrell, who both played their final season in 1947, the year Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier.

Howard’s career was shortened by a number of factors: He played three seasons for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues before signing with the Yankees in 1950. Then he spent the 1951 and ’52 seasons in the military. Then he spent the 1953 and ’54 seasons in the minor leagues, as the Yankees resisted pressure to integrate.

And when Howard reached the majors at age 26, his path to the starting lineup was blocked by one of the best catchers of all time, Yogi Berra, who collected his third MVP trophy in 1955, Howard’s rookie season. Howard made three straight All-Star teams starting in 1957, playing as a back-up catcher and outfielder. Not until 1960, at age 31, did Howard become the Yankees’ full-time starting catcher. He caught 1,138 games, more than Bresnahan but a few hundred less than each of the other Veterans Committee catchers.

But don’t cut Howard any slack for any of those factors that shortened his career. His achievements in the time he did have in the majors stack up favorably against the white catchers elected by the Veterans Committee. The whites averaged 17.5 seasons for their careers, compared to only 14 in the “majors” for Howard. But even with their longer careers, Howard had more runs than Schalk and Lombardi and more hits than Schalk and Bresnahan.

Lombardi hit more homers than Howard, 190 to 167, but the other three catchers were more than 100 each behind Howard. He also drove in more runs than any of the catchers but Lombardi.

For career averages, Howard was just a shade behind the others in batting, .274 to a combined average of .281 for the others. He also lagged behind them in on-base percentage, but was nearly 50 points ahead of the white group in slugging, with a higher OPS.

By any measure, Howard was a superior hitter to all of the other catchers but Lombardi.

Ferrell was elected mostly for his defensive prowess, but that was a strength of Howard’s, too. He won two Gold Gloves and retired with the record for fielding percentage by a catcher, .993.

Schalk and Bresnahan played before All-Star Games and MVP awards. Lombardi and Howard each won one MVP. But Lombardi’s and Ferrell’s seven All-Star selections didn’t match Howard’s nine straight All-Star seasons.

I’ve noted often here that post-season play and championship contributions don’t count at all in Baseball Hall of Fame selection (or they’d have to admit more Yankees). An illustration of that: Howard played in more than twice as many World Series games, 54, than the four white catchers combined.

Some of the outfielders I discussed haven’t been retired recently enough to get Veterans Committee consideration yet. That’s not an issue here. Schalk won 45 percent of the writers’ vote in his best year and was elected to the Hall of Fame 26 years after retiring. Bresnahan peaked at 54 percent of the writers’ vote and was elected 30 years after he retired. Lombardi was elected 39 years after he retired and peaked at 16 percent of the writers’ vote. Ferrell was elected 37 years after his retirement and never received even 1 percent of the writers’ vote.

Howard has been retired 47 years, longer than any of the white catchers elected by Veterans Committees. He peaked at 21 percent of the writers’ vote, better than two of the catchers.

From 1900 to the 1980s, the best catcher(s) of nearly every period of major league history are in the Hall of Fame. The only gap? From 1960, when Howard replaced Berra as the Yankees’ starter, to 1968, Johnny Bench’s rookie year. Who was baseball’s best catcher in that gap? Elston Howard.

There’s simply no explanation, other than race, for why those four white catchers are in the Hall of Fame but Howard isn’t.

Third basemen

Let’s go back to the Player A/Player B comparison:

- Player A played 14 seasons with these stats: .299 batting average, .357 on-base percentage, .436 slugging and .793 OPS. He scored 971 runs, with 1,978 hits, 344 doubles, 163 homers, 860 RBI, 120 stolen bases, 592 walks, one batting championship.

- Player B played 15 seasons: .305 BA, .365 OBP, .442 slugging, .807 OPS, 920 runs, 2,008 hits, 348 doubles, 163 homers, 860 RBI and 174 stolen bases, 605 walks, four batting championships.

Again, we’re talking borderline contenders. This time I’m measuring the five white third basemen elected to the Hall of Fame by Veterans Committees with Bill Madlock, who lasted one year on the writers’ ballot, getting only 4.5 percent of the vote. He’s been retired 28 years and has received no consideration for the Hall of Fame.

In the outfielder comparison, Players A and B were actually pretty close. Here, Madlock has a clear edge: besting the all the combined averages of the white third basemen and in all the offensive categories except runs and RBI.

The one Player A figure that wasn’t an average of the five white Hall of Fame third basemen was batting championships. They combined for one championship, three of them without having to compete with Latino or African American hitters (such as Madlock). George Kell and Ron Santo played their careers after baseball integrated in 1947. Madlock won four batting titles himself.

In fact, Home Run Baker was the only one of the white Hall of Famers we’re examining with more league titles in Triple Crown categories than Madlock, leading the American League in homers four years and RBI twice in the early 1900s (though he didn’t have to compete with any African American hitters). Kell was the only batting champion among the white third basemen. Jimmy Collins led the National League in 1898 with 15 homers. Santo and Freddie Lindstrom didn’t lead in any Triple Crown categories.

If you want to compare rankings among the six, rather than averages, Madlock didn’t lead all of the Hall of Famers in any of the categories I measured. But he also wasn’t last in any of them. He was second in four categories (OBP, slugging, OPS and homers), third in three (runs, hits and walks). He trailed most of the Hall of Famers in only three categories (fourth in BA and doubles, fifth in RBI).

You simply can’t make a case that Madlock doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame if it includes all five of these white third basemen. He was as good as any of them, better than most.

He’s been retired 28 years and received no Hall of Fame consideration. Maybe he’ll make it to Cooperstown someday. Kell was elected 26 years after he retired, Santo 28, Baker 33, Collins 37, Lindstrom 40.

Other infielders and starting pitchers

I’m not going to do a similar statistical study of other white infielders elected to the Hall of Fame by Veterans Committees. But I’ll just state emphatically that I think Cecil Fielder, Cecil Cooper, Andres Galarraga, Frank White, Willie Randolph, Lou Whitaker, Davey Lopes, Julio Franco, Davey Concepcion, Bert Campaneris and some other minority infielders would compare well with the white players at their positions elected to the Hall of Fame by Veterans Committees. (Also Dick Allen and Maury Wills, whom I discussed Monday.) The only minority infielder elected to Cooperstown by a Veterans Committee is Orlando Cepeda.

I’m also not going to deal with starting pitchers, since I earlier compared Luis Tiant, the best minority pitcher who’s being overlooked for Hall of Fame consideration. Vida Blue and Dwight Gooden had great starts to Hall of Fame careers, but sidetracked their careers by cocaine abuse. While their careers still place them in the borderline category, they’re not likely to get a break from voters at any stage of Hall of Fame consideration. (Raines and Parker didn’t really have borderline careers. They would be certain Hall of Famers if not for their cocaine use.)

Relief pitching

Here are the career stats of five dominant relief pitchers whose careers overlapped for six seasons in the 1980s:

- Pitcher 1 led his league in saves five times, played 12 seasons, had 300 saves, four seasons over 30 saves and a 2.83 ERA. He was a six-time All-Star.

- Pitcher 2 led his league in saves three times, played 22 seasons, had 310 saves, two seasons over 30 saves and a 3.01 ERA. He was a nine-time All-Star.

- Pitcher 3 led his league in saves four times, played 18 seasons, had 478 saves, 11 seasons over 30 saves and a 3.03 ERA. He was a seven-time All-Star.

- Pitcher 4 led his league in saves twice, played 24 seasons, had 390 saves, eight seasons over 30 saves and a 3.50 ERA. He was a six-time All-Star.

- Pitcher 5 led his league in saves three times, played 18 seasons, had 341 saves, two seasons over 30 saves and a 2.90 ERA. He was a seven-time All-Star.

I’ll tell you more about each of the pitchers shortly, but first try to guess which one isn’t in the Hall of Fame and hasn’t even come close. It’s the guy with the most career saves, most seasons over 30 saves and second-most seasons leading his league in saves, even though only one of the other pitchers had a shorter career. He’s tied for second in the group in All-Star appearances. He’s also the only African American of the bunch, Pitcher 3, Lee Smith.

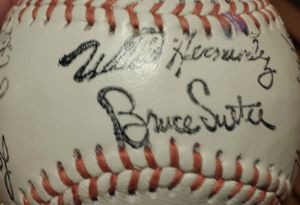

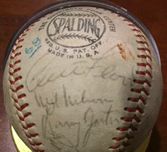

Bruce Sutter and teammate Willie Hernandez were among the Cubs who signed this ball, which my father gave my mother in the 1970s. Hernandez matched Sutter with a Cy Young Award and also was an MVP.

Pitcher 1 is Bruce Sutter, who pitched 1976 to 1988. His career was cut short by a nerve injury in his shoulder after he joined the Atlanta Braves, his third team. Sutter won the 1979 Cy Young Award and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006, his 13th year on the writers’ ballot. He had a 68-71 record.

Pitcher 2 is Goose Gossage, who pitched from 1972 to 1994. He had a 124-107 record, recording double figures in relief wins four times. He won election to the Hall of Fame in 2008, his ninth year on the ballot.

We’ll get back to Smith.

Pitcher 4 is Dennis Eckersley (and the reason that I didn’t post win-loss records in listing career achievements. His was 197-171). Eck started from 1975 to 1986 for the Indians, Red Sox and Cubs, going 20-8 his best season, for the Red Sox in 1978. His first bullpen season, 1987 for the A’s, wasn’t very impressive, going 6-8 with just 16 saves. But in 1988, he led the league with 45 saves, starting an incredible five-year run, capped in 1992, when he won the Cy Young and MVP awards, saving 51 games with a 1.91 ERA. He was a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 2004.

Pitcher 5 was Rollie Fingers, who burst on the scene anchoring the bullpen for the A’s in their 1972-4 championship run. In 1981, he won the Cy Young-MVP combo. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1992, his second year on the ballot.

I’m not saying that any of these white relievers don’t belong in the Hall of Fame. They all do. But Smith was clearly their peer, matching or exceeding their achievements in the very same era when they played. And in 13 years on the writers’ ballot, his peak has been 51 percent of the vote. If he doesn’t get over 75 percent in the next two years, he’ll have another five-year wait, then be eligible for consideration by Expansion Era Committees.

I should add that two other relievers of the era were clear peers of Smith and the four Hall of Famers, at least at their peaks:

- Dan Quisenberry led the league in saves five out of six seasons, tying him with Sutter for save titles, with more than any of the others. He was in the top three in Cy Young voting four straight years and absolutely should have won in 1983. His 1980-85 performance was the best prime of any of the six, better than Eck from 1988-92 and Sutter from 1979-84. But the Hall of Fame (except in Smith’s case) has a strong bias for longevity over peak performance, and Quiz almost vanished after 1985. Quiz made the Expansion Era ballot in 2013 but fell short of election.

- Puerto Rican Willie Hernández had an even shorter prime than Quiz, winning the Cy Young and MVP awards in 1984 and having two All-Star seasons after that. But he was a prime closer only for those three seasons.

Also in this series

This is the fourth of five posts I am writing about racism in selection to the Baseball Hall of Fame:

- Hall of Fame’s ‘Pre-Integration Era’ Committee perpetuates segregation

- Black and Latino players in the Baseball Hall of Fame were nearly all automatic selections

- Changing standards for the Baseball Hall of Fame always favor white players

Next: The Yankees integrated slowly and reluctantly.

Drug note: I do not address players whose Hall of Fame consideration is affected by suspicions about performance-enhancing drugs. Whether players have admitted or denied involvement or even been cleared in court, suspicion seems to be holding up Hall of Fame election for people of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds: Barry Bonds, Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire and many others.

Yankees note: This blog usually writes about Yankees. This week I am taking a broader look at continued racial discrimination in baseball, so I didn’t want to disrupt to note Yankee connections in the body of the post. I noted the Yankee connections of Howard, Williams and Combs, because they were important in that context. Other Yankee connections in this post: Gossage pitched some of his best seasons for the Yankees. Bobby Bonds and Baylor played briefly, but in their primes, for the Yankees. Felipe and Matty Alou, Lee Smith, Raines, Davis, Slaughter, Wynn and Ken Griffey Sr. played for the Yankees after their primes.

Style note: The Hall of Fame has had various committees and rules through the years to elect players who were passed over by the Baseball Writers Association of America as well as umpires, managers, executives and other baseball pioneers. I am referring to them all in this series as the Veterans Committee unless the specific context demands reference to specific committee such as the current era committees or the Special Committee on Negro Leagues. Baseball-Reference.com has a detailed history of the various committees.

Source note: Unless noted otherwise, statistics cited here come from Baseball-Reference.com.

Correction invitation: I wrote this blog post a few months ago late at night, unable to sleep while undergoing medical treatment. I believe I have fact-checked and corrected any errors, but I welcome you to point out any I missed: stephenbuttry (at) gmail (dot) com. Or, if you just want to argue about my selections, that’s fine, too.

Thanks to newspaper partners

I offered a shorter (less stats-geeky) version of the first post in this series to some newspapers. Thanks to the newspapers who are planning to publishing the in print, online or both (I will add links as I receive them):

- Daily Herald, suburban Chicago

- Lowell Sun, Lowell, Mass.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press

- Trentonian, Trenton, NJ

If you’d like to receive the newspaper version of the first post to use as a column, or would like a shortened version of any other posts in the series to publish, email me at stephenbuttry (at) gmail (dot) com.

[…] would certainly give the Yankees six minority Hall of Famers someday. Seven if Hall of Fame voters held Howard to the same standards it has held white catchers (as I noted earlier in this […]

LikeLike

[…] Sherm Lollar, Lance Parrish and Bob Boone — were nowhere near as good as Pérez at age 25. Elston Howard, starting his career late because of military service and racial discrimination, didn’t play […]

LikeLike

[…] my Oct. 8 post examining white borderline candidates who make it into the Hall of Fame and minority can…, I had sections on both Raines and Smith, which I will repeat here (with some minor editing because […]

LikeLike

[…] in my series on continued racial discrimination in the Baseball Hall of Fame, that era already has too many borderline candidates already in the Hall of Fame. Maybe some who didn’t make it are better than some who did, but those who didn’t […]

LikeLike

[…] as 1927, most of these players probably would be honored in Cooperstown: Kaat, Wills, Maris, Elston Howard, Minnie Miñoso, Matty Alou, Curt Flood, Bill Freehan, Roy Face, Rocky Colavito, Billy Pierce, […]

LikeLike

[…] primary teams for two Hall of Fame third basemen. The Pirates have Hall of Famer Pie Traynor and Bill Madlock, a four-time batting champ. The Cubs had Hall of Famer Ron Santo and Madlock. The Braves had Hall […]

LikeLike

[…] Howard, who had a better career than the white catchers chosen by the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee, played 227 games in left field, his primary position in 1956 and ’57, when Berra was still […]

LikeLike

[…] ready for his epic 1961 season. Mantle had two of his best seasons under Houk’s leadership. Elston Howard blossomed as an MVP. Houk started Whitey Ford on a regular schedule, and he dominated the American […]

LikeLike

[…] Comparing borderline white Hall of Famers with black and Latino contenders […]

LikeLike

[…] last year, he has no chance of reaching the 75-percent vote required for induction. As I’ve noted before, his career is indistinguishable from the relievers of his era who made the Hall of Fame: Dennis […]

LikeLike

[…] a lifelong Yankee fan because of Maris (and Mantle and Richardson and Ford and Yogi Berra and Elston Howard and the rest of the […]

LikeLike

[…] a lifelong Yankee fan because of Maris (and Mantle and Richardson and Ford and Yogi Berra and Elston Howard and the rest of the […]

LikeLike